Shuffling and permutations

How would you shuffle a deck of cards?

A couple of weeks ago I was talking to a friend about the problem of shuffling a deck of cards. His take on it was to do:

for i = 1 to n do a[i] = i

for i = 1 to n-1 do swap[a[i],a[Random[i,n]]My idea was:

for i = 1 to n do a[i] = i

for i = n to 1 do swap[a[i],a[random[1,i]]Both of them seemed reasonable, but were any of them correct?

And what does it mean for the shuffling implementation to be correct? It means that each of the possible permutations of the array (or deck) is equally likely. Which is equivalent to the problem of generating a random permutation of a given array.

This week I was flipping through Skiena’s “The Algorithm Design Manual” and landed in section 14.4 “Generating permutations”, and ended up spending my weekend researching this subject.

Permutations

As mentioned previously the problem of shuffling a deck of cards (or an array of distinct elements for that matter) is equivalent to generating a random permutation. A standard playing card deck has 52 cards, and hence 52! possible deck arrangements. After shuffling we want to make sure every one of those possible 52! outputs is equally likely.

How to do this?

For small arrays it is feasible (but not trivial) to generate all possible permutations and then randomly select one of them and return it as the output. The problem is that permutations order of growth is factorial:

- For 4 cards we have 4! = 24 possible outputs

- For 6 cards we have 6! = 720 possible outputs

- For 8 cards we have 8! = 40320 possible outputs

- …

- For 52 cards we have 52! = ~8.06e67 possible outputs

So this approach becomes unreasonable very quickly (factorially so!). There must be a better way.

On rank

A quick side-note, as I will be using this in my analysis. The rank of a particular permutation is its position in a given lexicographic generation order. The lexicographic order is the sequence in which the different permutations would appear if they were sorted numerically [1].

It’s easier to understand with an example. Let’s say we have 3 elements: {1,2,3}. The lexicographic order for its permutations is:

{1,2,3} -> {1,3,2} -> {2,1,3} -> {2,3,1} -> {3,1,2} -> {3,2,1}

So:

- {1,2,3} will have rank 1

- {2,3,1} will have rank 4

- and so on

In my experiments I will be calculating the rank of every permutation generated. A good shuffling algorithm will generate permutations whose rank is given by a uniform distribution, this is, every rank is equally likely.

Skiena provides a recursive implementation for rank calculation in [1], but I ended up using the simpler implementation explained in [2]

Shuffling in memory

A better way to do this is to do something similar to what we do in “Shuffle 1” and “Shuffle 2”, this is, randomly swap element of the array. As I said those 2 algorithms seem reasonable, so let me throw another one into the mix:

for i = 1 to n do a[i] = i

for i = 1 to n-1 do swap[a[i],a[Random[1,n]]Reasonable enough as well, right? So let’s put these 3 algorithms to test.

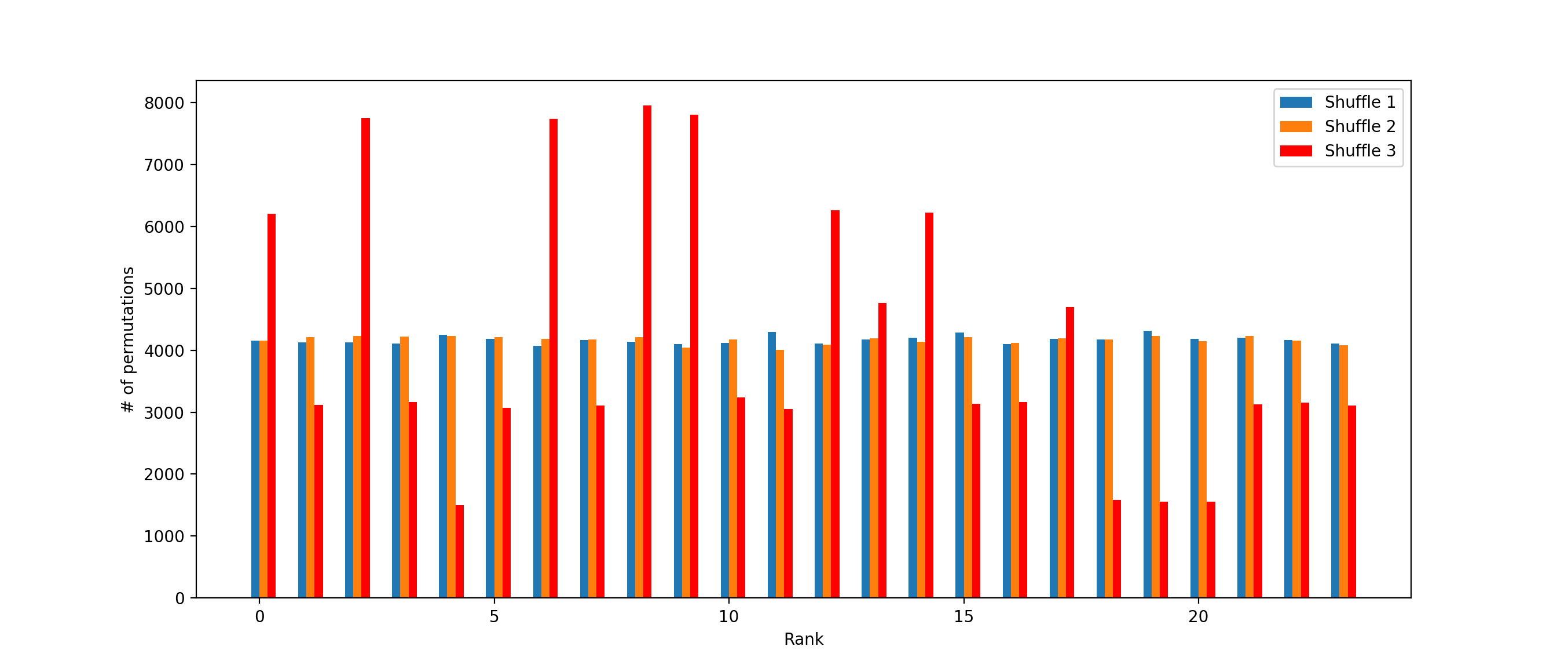

For every shuffling algorithm I will have an unordered deck of cards ({1,2,3,4}) that I will shuffle and store the rank. I will do this 100k times and I will keep track of how many times each rank has appeared for every algorithm.

If the algorithms provide real random permutations we would expect to see each rank to be equally likely.

Results

(Click to enlarge)

We observe that both Shuffle 1 and Shuffle 2 provide a uniform distribution of every possible permutation. But Shuffle 3 is definitely favoring some permutations over others. What is happening here?

Analysis

Let’s put all 3 together here for easier reference.

for i = 1 to n do a[i] = i

for i = 1 to n-1 do swap[a[i],a[Random[i,n]]for i = 1 to n do a[i] = i

for i = n to 1 do swap[a[i],a[random[1,i]]for i = 1 to n do a[i] = i

for i = 1 to n-1 do swap[a[i],a[Random[1,n]]As we can see the variations are minimal.

In Shuffle 1 we traverse through the array. At every point we find a random index between the current index and the end of the array, and swap the current element with the element in the random index.

In Shuffle 2 we traverse through the array in reversed order. At every point we find a random index between the beginning of the array and the current index, and swap the current element with the element in the random index.

We can already see these 2 implementations are equivalent.

In Shuffle 3 we swap the current element with a random element selected from the whole array. Strangely, this solution seems more random since each element can be swapped multiple times. But we already see that it won’t provide a truly random permutation. Why? And why do Shuffle 1 and Shuffle 2 work?

Jeff Atwood explains it beautifully in his article “The danger of naivete” [3].

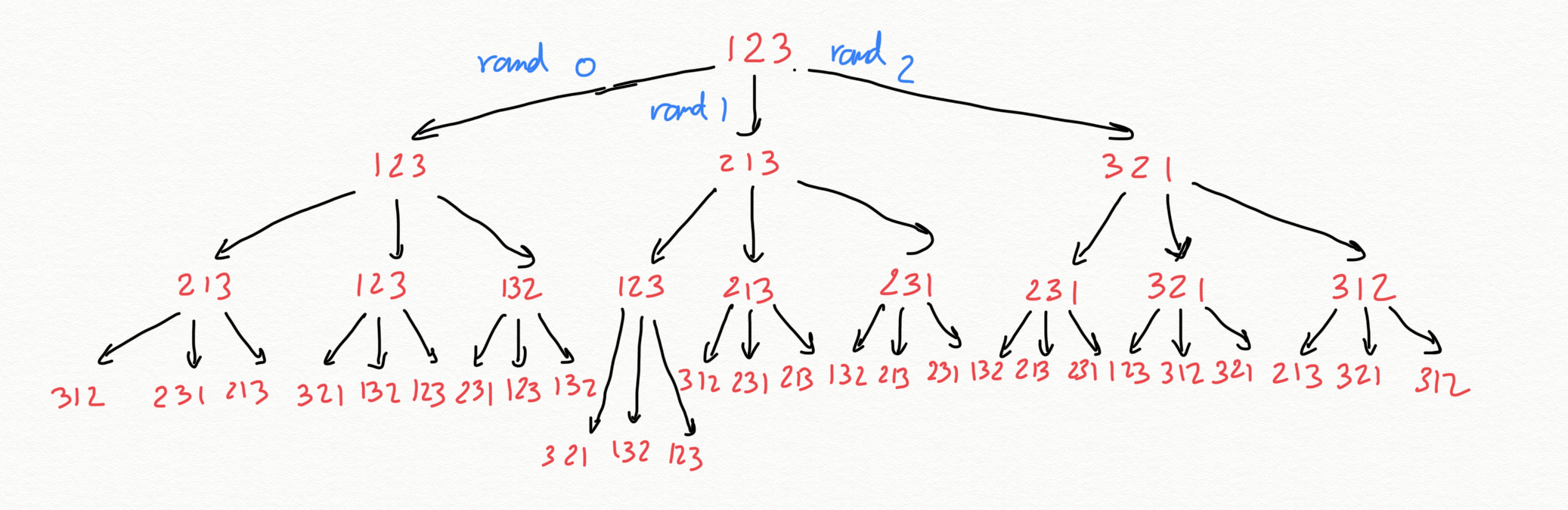

Let’s say we have a 3 card deck. Shuffle 3 will do 3 shuffles: rand(3), rand(3), and rand(3). For a total of 3^3=27 possible outputs. Strange, since in 3 cards we only have 3! = 6 possible permutations. On the other hand shuffles 1 and 2 will do 2 shuffles: rand(3) and rand(2), for a total of 3*2 = 6 possible outputs. So far what we would expect!

Let’s see what the outputs for Shuffling 3 are:

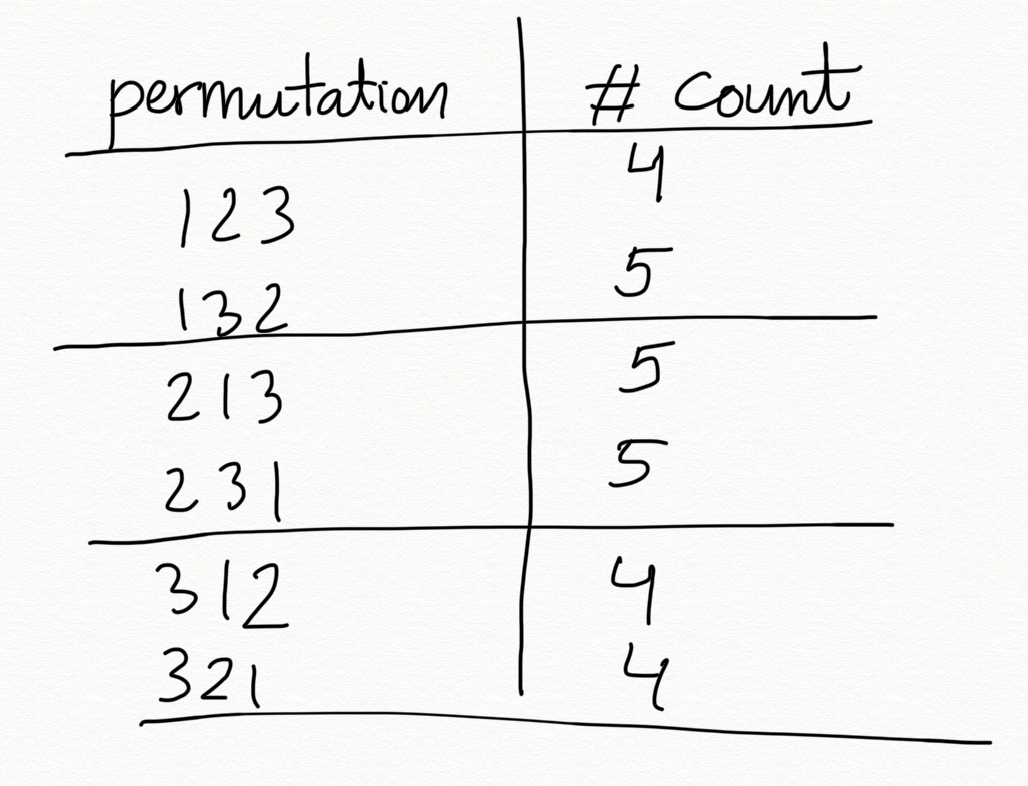

If we count each occurrence we have:

So we see clearly that with “Shuffle 3” each possible output won’t be equally likely. Therefore, this is not a suitable algorithm to shuffle or generate random permutations.

Fisher-Yates/Knuth Shuffle

“Shuffle 1” and “Shuffle 2” are an implementation of what is known as Fisher-Yates[4] or Knuth (Algorithm P)[5] Shuffle.

Originally developed as a manual method in the 30’s by Fisher and Yates, with time complexity O(n^2). The above implementations reduce it’s complexity to O(n), by swapping the selected elements and reducing the random index range at every iteration.

Doing a similar analysis as the one showed above would yield the following possible outputs, each one with a count of 1:

{1,2,3},{1,3,2},{2,1,3},{2,3,1},{3,1,2},{3,2,1}

Which is exactly what we want from a random shuffle.

Takeaway

We have seen that minimal changes in the implementation of an algorithm can yield results with undesirable random properties. The difference is subtle, easy to miss, and it’s not evident which implementations are correct and which are not. It’s better to stick with standard libraries when dealing with problems that require truly random results.

References

[1] Steven S. Skiena. 2008. The Algorithm Design Manual (2nd ed.). Springer Publishing Company, Incorporated.

[2] https://stackoverflow.com/questions/39839119/rank-of-a-permutation

[3] https://blog.codinghorror.com/the-danger-of-naivete/

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fisher–Yates_shuffle

[5] Donald E. Knuth. 1997. The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 2 (3rd Ed.): Seminumerical Algorithms. Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc., Boston, MA, USA.